The Fight to Repair - Part 6: Legislation Loopholes, Eco Black Mirror, Chunky Fashion, and The Case for Standardisation.

Follow articleHow do you feel about this article? Help us to provide better content for you.

Thank you! Your feedback has been received.

There was a problem submitting your feedback, please try again later.

What do you think of this article?

Legislation alone ain’t gonna save us. It’s one part of the systemic change, and Designers have a significant role to help Legislation have more impact, and Consumers adopt better habits. The Right to Repair is a movement, not just a ‘nice to have’, it is arguably a barometer of ethical consumerism.

As part of a series of articles, this one will focus on:

- Spoiler: The new legislation isn’t gonna change the world, but it might encourage designers to make better products, albeit a little chunkier, but they will last longer.

- Design Tips from interviews with Designers: How you can make things more reparable, compliant, and possibly even save money for your company.

- The case for Standardisation of Lithium Batteries.

- Design discussion on some of these ideas and issues, with renowned Product Design, Andy Carr.

Batteries and Legislation.

Pure Fear or FOMO - depends a lot on your perspective of Innovation...

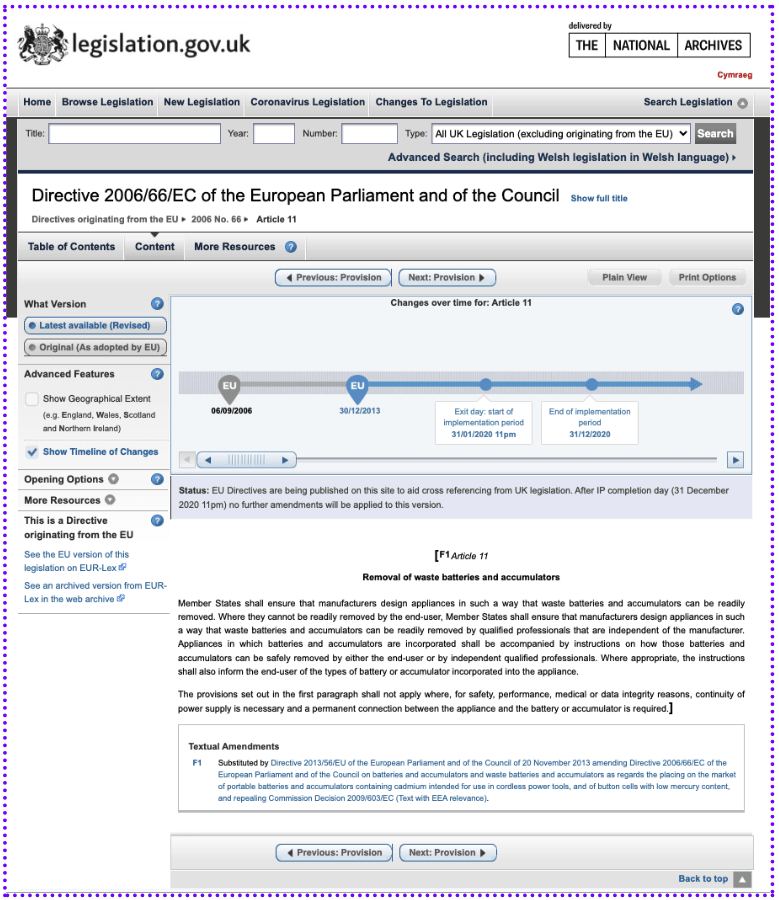

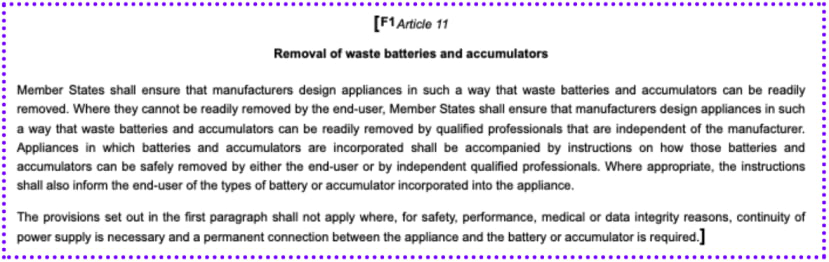

As I read it, the most pertinent legislation for the EU - and arguably the World, is the 2006/66/EU directive. I believe it’s intent is to be around limiting clumsy, causal and careless use of myriad LiPos batteries in products, with an emphasis on the repairability - if not by the general public, then at least by a repair shop or competent individual. With a knock-on effect being that end-of-life processes benefit from batteries also being easily removable (i.e. not sealed units or glued in).

Before you get excited that everything electronic is going to go all modular, and Apple will automatically acquire Fairphone, and make ‘plug and play’ components to switch out like the good old days of DIY desktop computer building. Nope, those days are gone, and the likely way forward is a bit more prosaic.

Before we begin, some useful links:

- The Official Document: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eudr/2006/66

- The ‘crux’ of the matter: Article 11: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eudr/2006/66/article/11

- A Q&A Digest (not legally binding) but in simpler English(!!) from the European Commission: https://www.epbaeurope.net/assets/European-Commissions-guidance-document.pdf

Let’s get into the details, and look at some point that caught my attention...and may be useful to you at work and as an interested consumer.

From EC Digest: Why this is a “Work in Progress”:

This speaks to reality that Legislation does not ‘win first time’, and if you consider that policy makers will always lag behind the cutting edge of technology by 5-10 years (or more), and are likely impeded by lobbyists, as well as economic pressures like recessions, it really does take a lot to drive through change. So waiting around for ‘Legislation to fix this’ is really not realistic as the only approach.

With that said, it is a ‘backstop’, and personally I see it as something that represents the bare minimum, and more proactive companies may do well to consider how if they are needing to significantly revise a product, better to ‘future proof’ it for more than just this current iteration of the legislation.

As much as companies might bemoan legislation making it hard for them, objectively, the statistic of 45% of batteries in the EU in 2002 ending up in Landfill or Incineration sounds like something that is going to catch up with us in the years to come. These chemicals are not just a waste, but a threat if they start to build up in water and food chains. You don’t have to be a geological expert to know chemicals leaching out of landfill is a frightening consequence of our unchecked consumerism and e-Waste.

From the Directive: Why it is “Minimise” and “Reduce”, not “Eradicate” and “Replace”:

I would say the language in this is still pretty placid, and is less ‘burning platform’ than you might expect as a member of the general public. The reality is that Legislation works ‘hand-in-glove’ with what the companies and economics can withstand.

The Complex Dance of Legislation, Industry and Consumers:

Some Anecdotes from Previous Work.

When working at Sugru, I asked a scientist who writes legislation on Glues (as Sugru was a ‘glue’), “Why, if Epoxy is so bad, have we not banned it?” His reply was in essence that ‘You can only ban something when you have a credible alternative - right now, there is no scalable, cost-effective, and approved alternative...yes there are some ‘eco-epoxies’, but they do not readily tick all those 3 boxes - meaning that companies have to reconcile the extra cost, complexity or approvals to ‘swap out’ the Old with the New’.

He went on to explain that innovation usually comes out of incremental improvements, or a breakthrough that upends an entire sector. The disruption can be a Bill/Legislation passed by ‘brute force’, but often this is because politicians (and policy makers) have a credible alternative up their sleeve.

If you look at Epoxy, take the car industry - consider how much stuff uses Epoxy (a quick stat: car driving in EU alone is around 0.5 billion tonnes of Epoxy ), and if you were hypothetically forced to use an inferior or vastly more expensive alternative - your whole business model topples, and who is going to foot the bill? Sometimes the Taxpayer, if public support is really behind it, or if economically critical to some other goal, it can be justified by governments to be ‘for the greater good’ - but this ‘good’ is a multidimensional thing, and encompasses not just ethics, but jobs, industry, and much more.

A Powerful Fable of Radical Sustainability Needing Tread Carefully:

Film: The Man in the White Suit, 1951.

Perhaps one of the most lucid allegories of this tension is the film, The Man in the White Suit. Released in 1951 follows the breakthrough of an idealistic scientist who created a thread, textile, and then suit - which NEVER needs washing and NEVER breaks. You only need one and it lasts FOREVER!

Who wouldn’t want this glorious utopia?!

The kicker is that the factory sells as many as people can buy in year one. Record profits. Bonanza!

Year two...you guessed it - zero sales.

However, the film goes beyond just interrogating the capitalist greed of ‘The Man’, and articulates our social dependence on the wider consumerist model.

The scientist had been trying to impress a local worker’s rights activist. Initially he was a hero for the sudden boost in employment and that the factory even paid extra to get through orders asap. However, with sales now down - those people were jobless.

Further still, the old ‘Washerwoman’ who used to wash clothes for the rich was also destitute and nearing starvation. Already poor, she lost her only viable income source.

Now despised for his ‘brilliant creation’, the people start to turn on him, from all sectors. He is saved from a near beating, when in the kerfuffle his suit tears, and falls to bits. For some unknown reason, there is a flaw in the chemistry and now the fibres and hence suit falls into pieces. In a strangely emotional scenes he is stripped of his clothing, his glory and his friendship by a seething mass of people - giddy with elation that things are blessedly going back to the ‘good old ways’, where labourers toiled away, big corporations got rich, and washerwomen at least had jobs.

As much as I’m a fan of Charlie Brooker, I think this was perhaps the first Black Mirror episode that truly ‘reflected back’ at us our apparent hypocrisy and oversimplification of the circumstances on which our economy is based, and how much we do or don’t do to affect the change we claim to want.

Like Black Mirror, The Man in the White Suit is a sobering tale, which is hard not to feel a little raw from the frankness of the message within. We have a lot more soul searching within ourselves, not just searching for someone to point the finger is arguably the message.

Extending Life.

Getting back to Batteries, I feel this analogy resonates - we have considerable economic, industrial, design and social ‘status quos’ to overturn if we want to see a better system ‘switched out’.

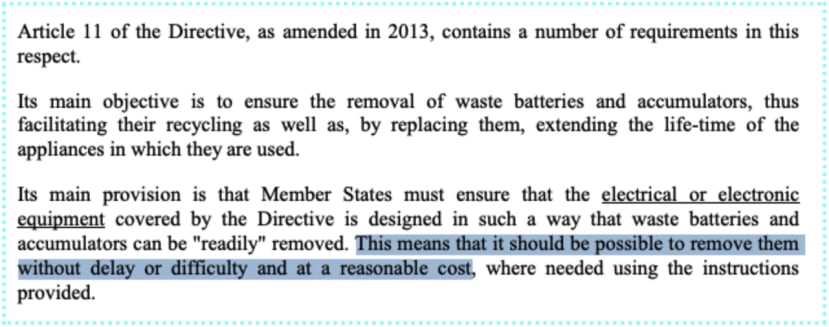

From The EC Digest:

As for the manufacturing imperative - this will need to be harmonised in terms of cost, complexity and compliance to even be considered, and even then, it likely needs to be ‘even better’ (cheaper, performs better, etc.) to be adopted at speed, and be worth the risk of trying anything new!

Why Designers Should Think Like Lawyers Sometimes.

Having worked on Patents for many years at Dyson, Sugru and LEGO... one starts to develop a ‘Times Crossword’ knack of spotting when something is hinting at a subtext. Often in a list of Patent Claims you’ll get to number 34 out of 67, and realise “aha! THIS is what the meat of the commercial intent!”.

This is not illegal, but a competent patent attorney will incorporate seemingly innocuous claims, which are in fact strategically critical to their future. For example, one might suggest that a device can be used in 10 different ways, one of which is how you are actually doing business, 8 are to prevent not-great-but-still-annoying competitive alternative, and one more might be your next generation of innovations, coyly protected in this medley of claims. The intent is to not give the game away, but still get your future protection baked into this upfront.

Reading Between The Lines: The “Third Party Loophole”.

Detail:

Coming back to the above Article. What stands out for me is not the ‘notion’, but the ‘opportunity’ around third party repairs.

To those with optimistic outlooks in life, this may read like legislation telling companies that they MUST allow their batteries to be removed by a third party repair shop. You might be forgiven for thinking that this means companies like Apple MUST allow consumers to go get their screen replaced by ANY “qualified professionals that are independent of the manufacturer”. What this does not legislate against is the practicality or affordability of such measures.

I would imagine that it is perfectly acceptable for Apple to say “Ok, sure, you can get your screen replaced by an approved repair shop - but a. We will bury them in training, that is such a huge outlay, they probably won’t be one anywhere near you, and b. We didn’t say it would be cheap - it could cost you say two thirds as much as it was new!”

To my eyes, the line “safely removed by either the end-user or by independent qualified professionals” seems to have a legal undertone of “if it can’t be done safely by the end-user...” - I personally think this implies a risk-assessment would be conducted internally by any company, which will conclude that users should not touch a battery which can explode! The natural implication is that they are ‘funnelled’ to the second statement of “...by independent qualified professionals”. And so if a company wants to make it unsafe (this does not mean dangerous - just not safe for general public), then the open-endedness of the 3rd party repair shop offering does not state anywhere that this has to be a “cheap or compelling price, perhaps commensurate with a percentage of the cost of the Bill of Materials for the item itself”, so companies are at liberty to also ‘bundle’ components together, so that if say your keyboard is broken, you have to replace the trackpad as well (search Apple again for this).

A Worked Example: Would You Become A Repair Shop?

Let’s say Apple had to publish that its Bill of Materials (ie cost to manufacture) for an iPhone Screen was say 33% of the total cost. If we assume 40% margin on a phone at $1000, then let’s say it costs $600 to make, then a screen replacement at 33% is $200, allowing the Service Shop to charge around say more than 40% mark-up in labour - ie $80 Labour per Screen Repair.

Now, if the repair itself requires the service person to have spend 100 hours being trained (and likely has to pay to be trained also), and the repair itself takes say 1 hour, you can appreciate this is ‘slim pickings’ when you consider the repair shop also has to guarantee their work to be good, and absorb the cost of any accidental damages they cause. Suddenly £80, after all the hassle, is hardly worth it, certainly in most developed countries.

This is a long way to say, a company might be compliant with 2006/66/EC - but it does not mean that consumers are going to find the effects of it transforming their Right to Repair experiences overnight, not just because it’s prohibitively complex (few will sign-up to do this, other than very big companies), but prohibitively costly also. The notable exception would be companies where the ‘value’ is in the continual operation of a machine, such as Rolls Royce - where the airline is not charged for buying an entire engine, but rather by the air-miles flown - so they are incentivised to keep it in good working order for as long as possible, as their business model is not to ‘switch out’ a new engine every 2 years!

The legislation arguably does not force a company to offer an ‘easy’ alternative to repair or replace something if broken, nor does it say that a screen should be designed that it is not tethered/glued/welded to a bunch of other stuff that make the ‘unit’ expensive to switch-out, even if it’s only the glass that is broken.

From the EC Digest:

Although the digest certainly works with the ‘intent’, as it claims not to be ‘legally binding’, I worry that despite stating that ‘it should be possible to remove [batteries] without delay or difficulty, and as reasonable cost”, (‘reasonable cost’ is a moot point that would need a trial to resolve I suspect!). I cannot see enough specifics to imply this has to be financially lucrative for someone to run a Repair Shop, as opposed to another less fraught enterprise, or that the resulting cost will be deemed ‘fair’ by the consumer.

It is hard to say whether future updates to this legislation will tackle the ‘bundling’ issue, and ensure that if you break a screen, you replace the screen, not a screen+sensors+vibration motor+this+that etc. which drives up the ‘fair price’ for the repair.

So What About DIY Repairs (with respect to Legislation)?

Apple is well known for wanting to restrict unregulated 3rd party Repair Shops, and having personally been in the position of designing new products, and coordinating all the safety testing and compliance for them, I’m honestly sympathetic to the issue of quality assurance... If a user were able to put a substandard replacement battery in an iPhone, and it blew up in their pocket, and caused horrific burns, I think we can all be honest that the headline would read “iPhone exploded in Teenager’s Pocket - Scarred for Life”, and a. the said Teenager may not ‘fess up’ that it was their dodgy replacement that caused it, and b. Even if they did (poof goes your [fraudulent] lawsuit against Apple btw), the PR damage is arguably done, and few if any media companies will do a follow-up to say in effect “well, it kinda was their fault - sorry Apple we shouldn’t have been so quick to blame you!”. And c. being honest, would we click it! (We perhaps also have to admit that we don’t always click on the nuanced story over the sensational ones.).

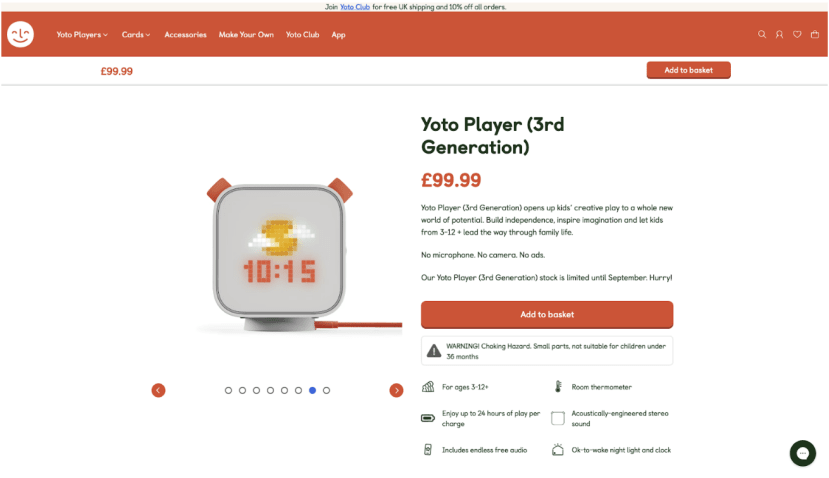

A Thought Experiment With An Existing Product: Yoto Players + Replaceable Batteries.

To perhaps give a product-based example; Yoto Players are, in my opinion, probably some of the best designed products I’ve seen that are also pretty well considered for ease of repair by the manufacturer (lots of screws, not too much glue, etc.). You can send yours back and get it repaired if you have any issues. They are not offering user-repair or even third party repair, but I think when you consider that this is a product that your young child may well take to their bed at night, you really don’t want to risk a battery fire. So I think they have it ‘as good as it can be - all things considered’.

To be clear, I am not pushing Yoto to do that overnight, as it’s a complex and costly decision for a Startup, but it nonetheless seems a great potential ‘poster child product’ if it did have user replaceable batteries and a good after-sales battery replacement scheme.

For the record, these are my own opinions on the matter, and are not representative of Yoto’s.

The idea to replace a Yoto battery clearly falls into a grey area. The company is pretty new, but an irony of this being such a well made, award-wining and 5-star reviewed product - is that in perhaps 5 years or so, a Yoto purchased in say 2020, may be on it’s 3rd hand-me-down to a new family, but the battery is dead, it only holds charge for say 10 mins and then dies. Many people will simply buy a new Yoto player, and indeed, it’s designed such that the battery can likely be recycled easily by a battery recycling plant.

However, what about those people, who are considering ‘Right to Repair’ as a ‘right’!?

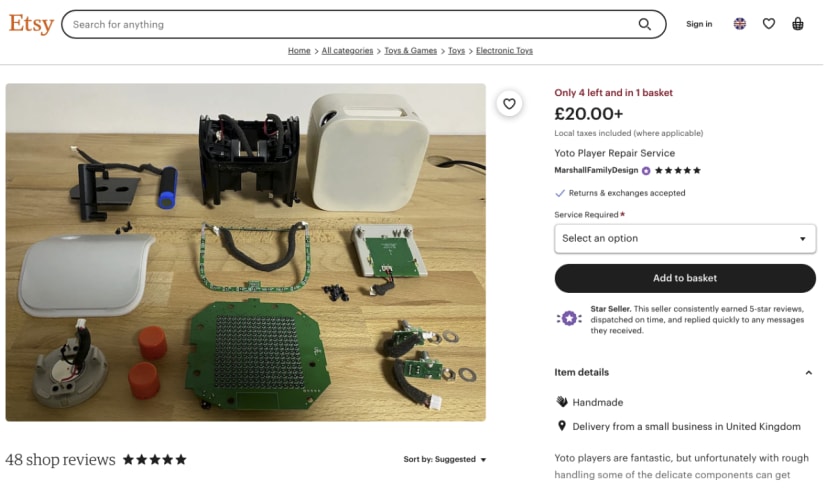

I had a google, and sure enough someone is kind enough to be selling parts for repair on Etsy. Etsy is of course not a third party repair shop, but is a place you may to find well-meaning, eco-conscious types, who care about small companies and products like this, and are likely motivated by best intentions.

Tip Tip: FCC.io website is a great ‘designer’s secret’: It is a compliance website that tests consumer appliances (usually with batteries), and does a pretty good Teardown - so you don’t have to! Yoto is no exception, with Gen 1 and Gen2/Mini being easily searchable. A great way to check internals, spec’s, components, etc. for reference without doing it yourself!

Getting back to the Yoto Spares - chances are these are legit parts, but for the record - these are not endorsed by Yoto, the seller in not claiming to be an authorised service shop. So it falls pretty much into this grey-area of ‘good intentions’, which is perhaps tolerable if you’re a startup making thousands of products, but not viable if you’re at the scale of Apple selling millions of products.

I can’t verify this, but chances are, this is someone who has got legit spares from perhaps factory seconds, or a charity shop, etc - perhaps with scratches or cosmetic damage, but they work fine. Given that the connectors require no soldering, and are reliable JST plugs, chances are they will work fine. But one can appreciate how this sort of thing is really only tolerable with smaller companies, where the likelihood is these probably are genuine parts, as the market is not so big to make it worth the while of bad actors - yet.

This is likely something that companies like Yoto will encounter in future, as they grow, and their products are still in use, but perhaps the Lithium batteries are failing. It’ll be a complex path to walk, as although they could offer you a replacement Lithium battery, it would not be able to be sold as shown above, as this and would need to be manufactured like the ‘old school’ batteries you had in pre-smartphone era Mobile phones which were not just replaceable, but replaceable by a non-professional.

Again, this is just my speculation, but I do wonder if Gen 4 or the Yoto Player might have a User-Replaceable battery? If it does, the product will have to go through more compliance, it will cost more to make (will this be passed onto the consumer?), and they will have to figure out how to ship replacement batteries safely and legally to users (which is not trivial in the UK and requires considerable investment) They may even have made the decision to take the old battery back (again, a cost in postage, and industrial recycling).

However, I suspect that it will be ironically a mix of titans like Apple that resolve some of the huge issues, but also beloved companies like Yoto that sway public sentiment, and can afford to do this because their brand represents more than just a cute mp3 player, it’s arguably a ‘lifestyle product’ that promotes children’s imagination and love for stories, and has a loyal and ethically minded community who will likely support it, if it’s say 10-20% more expensive, but twice the price - eek! Perhaps the business model will shift from the product itself, to more the media (story cards), in the way a Printer is really only profitable when you buy many more Ink Cartridges.

Inevitably, there will be a ‘sweet spot’, and consumers need to ‘put their money where their mouth is’ to a certain extent as much as waiting for ‘legislation to have more teeth’. As with my story about Epoxy - when a credible sustainable alternative comes along, we do need to recognise it may be more expensive, and a bit inconvenient / more complex perhaps, but we do need to consider what message we send if we only buy cheap disposable products which were not even remotely designed to last, and be reused again and again.

There appears to be similarities to the Food Industry: If we consume more plant-based protein, industry will follow, and if Michelin Star chefs create more tasty and trendy recipes for plant-based dishes, consumers will eat more vegetarian dishes, etc. but who is going to 'make the first move' when it comes to Electronics where the ability to influence the global supply chain is arguably more difficult to affect change in.

So What Companies Encourage User-Replaceable Batteries?

For some reading this Blog series, and screaming FAIRPHONE HEADPHONES at the screen, yes, it has been on my radar, and having met some of the engineers behind some of its design, it’s certainly not lost on me that this is a notable company, with some exceptional products, which bring a lot of these themes together.

Arguably without unpacking a range of considerations, it would appear glib to just say ‘be more like Fairphone’, but honestly after looking back and forth through all this, it’s hard not to arrive at a conclusion that having user-changeable batteries (as well as a bunch of other spares) for products which honestly have the space to house them seems a no-brainer for companies who have the brand-momentum around sustainability to cope with the ‘eco-tax’ of such devices being usually a bit more expensive and let’s be honest, sometimes left a little lacking slightly in other places such as performance.

The mighty iFixit did a review of Fairphone’s Fairbuds XL, and in short, they are just great in terms of replacement of the battery. They have it all set up:

- Brand love / people who can afford the extra cost.

- Product size / tolerance can actually cope with the extra space needed to do this.

- Engineering complexity / user conventions - Pro Headphones are up for Repairability.

- Cost is tolerable as an overall percentage of the premium £250-£300 product.

Despite iFixit being 100% qualified to state the repairability, their authority on it being ‘great noise cancelling’ is not really seconded by some of the hard-core ‘audiophiles’ out there. To be clear, even with reviews that of course would consider Fairphones the ‘darlings’ of this emergent product culture - namely the Guardian, even they concede “They manage higher pitches such as typing and background chat in an office a little better than many, but can’t quite replicate the cone of silence produced by the best in the business from Bose and Sony”.

They still award them 5 stars like iFixit, but I don’t think Fairphone has to be overly apologetic for not doing an end-run on Sony and Bose, who have been in the ANC game for decades, when Fairbuds are clearly 9/10 or even 9.5/10 on Audio and ANC (for this price point), and a blistering 11/10 on Sustainability! As well as being genuinely nicely designed. Even if you don’t wish to signal too hard in Jazz Green, they come in Jazz Black for the more understanded eco-warriors out there.

Back to The Yoto Example...

Getting back to Yoto - In terms of ideology, I could conceivably see them doing a ‘Fairphone/Fairbuds-style User Serviceable Battery Replacement’ in a few years time, and why not? The brand ‘fits’, [at-a-glance] they potentially have ‘space’ in the product, and it seems plausible that their consumer base would love it! Furthermore, their business model is not just about the unit, but also the audiocards, and this fits the ‘Printers and Inks’ model, so taking away some of the financial worry that if they sell less Yotos per year, they are doomed. It would also take away the burden of having to certify the LiPo batteries for consumer use. However, to play Devil’s Advocate, it may be that the worry around LiPos are simply too great for a product that a child may well take to bed, and if they can’t control the risk of a third party ‘dodgy’ LiPo being used, it may well be that a Rechargeable NiHM Battery may well be a safer bet.

Above: A crude mock-up of how any given consumer product, in this case a Yoto Music Player (wireless speaker, with a Lithium battery), could be re-fitted to have either serviceable Lithium or NiMH batteries to extend the lif of the product. [These are not endorsed by Yoto, and are a work of fiction/discussion].

A simple differentiation of ‘intent’ repairability may well be that if it’s a LiPo it will need Service Screws (these are generally assumed to be the tools of a professional, and a repair shop, or a competent engineer who understands this is going beyond general public interaction). Conversely, if they went down the already standardise rechargeable battery route, and used say 3x AAA Duracell 900mAh 1.5v batteries, these come with a healthy 5 year shelf life and arguably could be serviced by the general public - and hence the ‘cross’ head screws being permitted. It’s true that this may add a few millimetres to the back of the product, but arguably this feels ‘on brand’ and is perhaps not instant death to the production cost and logistics of the products.

The Price of Miniaturisation.

Conversely, when you look at Apple Airpods, this to me feels like not just Apple, but the entire industry has ‘painted themselves/the planet into a corner’, and unlike the above examples, it is not easy to add a ‘user serviceable screw and flap’ to make the batteries under serviceable. In a weird way, I wonder if it is possible to consider a ‘bulky-but-proud’ countercultural movement, with opinion leaders behind it, as companies who do go down this route, likely cannot make products as compact, so need to own the ‘chunkiness’ in many ways.

How to ‘Embrace the Chunkiness’ of User Serviceable Batteries / Products.

If the fashion industry and mass media have been challenged in recent years for the supposed ideal of ‘slender is best’, perhaps a little more curvaceousness in a product is also okay, especially if overall the result is a more balanced outcome, and not just a ‘pedigree racehorse’ of the Industrial Design elite. In this regard, Fairbuds XL really are a fair provocation as to why not getting them if you profess to care about the planet, and like myself, need to ‘really live with it on a daily basis’ to have that ideology permeate my work ethics and to keep thinking ‘why not fairphone this?’ when in a product meeting.

Indeed, the Elephant in the Room with the Fairphone’s 5th generation phone - is not so much that it’s not a good [hardware] phone - it is (be honest now) - but rather that Apple has many many features, services and UI/UX things which many (myself included) are reluctant to give up, even at the promise of a more ethical, and really quite enjoyable product that I can upgrade. Having phoned around a few of my liberal professional friends in the tech industry, to our shame, this is a prevalent omission - and it’s highly likely Apple has focussed-grouped the heck out of this to know how many more years it is before people would make the switch. If Fairphone can guarantee it’ll do Airdrop, iCloud backup [family photos especially], and nail Security/Privacy - and then create a ‘Migrate’ button, I’m honestly in. You can hold me to this. But this also illustrates why ‘design’ is not just about the ‘plastic parts and LiPos’, but the entire user experience / ecosystem, as Steve Jobs was so fond of saying. Many of us are ‘tied in’ it seems.

My point here is that the nuance between Fairphone and Fairbuds XL is a key one. There is little holding me to my brand of headphones, so long as the Audio and ANC are ok, and the fit/feel/style is good. Fairbuds XL do this - hence I would 100% have ordered a pair, had I ironically not just fixed my broken ones, so I’m in an ethical quandary here - but seriously - in principle, my next headphones will be Fairbuds XL, not Sony or Bose or Sennheiser....unless they catch up on the R2R agenda (in which case Bas van Abel, CEO of Fairphone has really ‘won’ the battle in that product sector at least).

If you are designing an existing product, and have the space, and potential brand re/alignment (to absorb the cost), or indeed the business model is not all about the product per se, then this really does seem a good time to evaluate the opportunity to get ahead of competition and innovate it into the next generation of products.

The Case for Standardisation.

I read from a few sources that although batteries were created originally for a mixture of consumer goods like flashlights and military purposes. The Eveready Battery Company, founded in 1906, standardised AA dry cell batteries in 1907 and the smaller AAA in 1911 now known. It’s interesting to know that only a few years later in 1924, Duracell came in with a new chemistry - ‘Alkaline’, which is arguably the successor. Although I doubt Lithium Ion / Lithium Polymer battery standardisation will happen overnight, one would hope that in this modern world, it’s plausible that if Duracell can essentially rewrite the rulebook (in wartime), one would hope the climate crisis is sufficient stimulus to consider radical rethinking of our power storage and recharging technology.

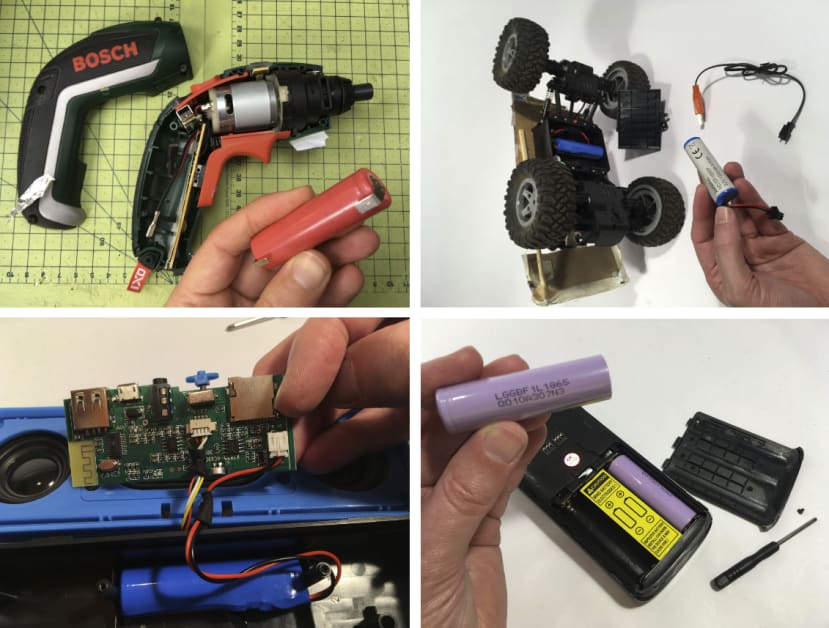

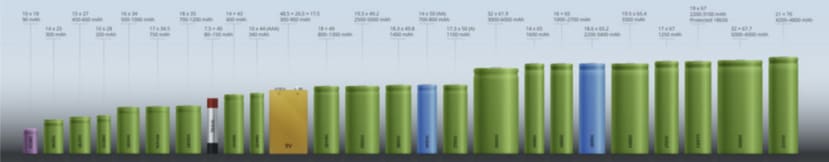

To give some perspective on the proliferation of types/SKUs/forms/specifications, one only has to have a quick look at any of the prominent battery manufacturers/distributors. The image above shows a fair selection of Lithium Ion cells, which cover many consumer goods, and in clusters even make up some pretty heavy industrial batteries, from tools (<10 cells), to e-scooters (10+), to cars (100+).

A casual appreciation for statistics will tell you that managing 100+ cells is a more complex bit of hardware, than 1 or 2 cells. For example, suppose 1 cell ‘dies’, how does the system ‘carry on’, and alert/neutralise it. This requires some advanced monitoring of the Battery Management System (BMS). But for the sake of this discussion, I’d focus on small consumer appliances, where it is single or a small number of cells where this is not such a strain on engineering complexity!

In addition to the Yoto Player only needing 1 Li Ion cell, I rummaged around my home, and tordown a few things to show just how common these cells were! Screwdriver, RC Car, WiFi Speaker, WiFi Doorbell - all 18650 or a close approximation of it. Indeed, I want to stress that even the WiFi Doorbell has not used a ‘bigger battery’ - but just has two 18650 Li Ion batteries. Job done!

So getting back to Lithium Polymer (i.e. the ‘pouch’ shaped variety with wires, not the ‘round cell’ variety...though exceptions exist), these for some reason go from less than 50 varieties like Li Ion, to over thousands! Not to single out any company in particular, but from a cursory internet search - LiPol Battery Company offers a staggering 5000+ models.

This might sound fair enough, but I’m lost as to why...

As tempting as it is to brush this off as ‘choice is helpful’ I think designers (myself included) need to be a bit more self-critical if we should also encourage more and more tiny differences between models/SKUs.

Above: Some pretty negligible differences in SKUs, some arguably less than 'tolerance' rated on specifications.

If one looks at the 7.0-7.9mm thickness range, this has completely different SKUs with only ±1mm or ±2mm difference in length, or ±5mAh difference in capacity. Are we seriously saying that our products are so precise that we can’t cull/prune some of these down a little bit?

Even going back to the example of my Sennheiser headphones, there are other OEM batteries with trivial differences from the 413645 by a few millimetres in width and length and a few tenths of millimetre in thickness. As someone who has designed products to industrial tolerances, most plastic parts are not so high tolerance that if SKUs were more limited one could not find a ‘close enough’ battery to suit the needs. The fact that I was able to get a 57% higher capacity battery and still just about fit this inside really illustrates this is not rocket science tolerances, and really, are you working to an unnecessarily tight Cpk tolerance - if so, why?

To be clear, I’m not saying designers only need 10 battery sizes, as of course this would be creatively stifling, but we should certainly trim back the 5000+ that are evidently out there, most of which are perhaps ok to consolidate into less than 100 SKUs of the most in-demand form factors and capacities.

An important point to note, is that one cannot casually put LiPo batteries in parallel without a good Battery Management System (BMS), (as mentioned in the Adafruit blog), as they can have different ages/health, so when combining to make higher capacity at same voltage or higher voltage at the same capacity, care should be taken on designing the BMS circuits. However, with care, cells can be combined and so reducing the need for too many SKUs.

OEM for User Serviceable Batteries.

What occurred to me when looking at Fairphone’s replacement batteries, is that they are arguably ‘generic’. Even their headphones battery is 800mAh. Only 100mAh more than the Sennheiser ones. My point is that Sony may need more, Bose may need less - but they are all in the similar ball-park, and arguably any of the other companies could incorporate a Fairphone Fairbuds style battery into their design, (in an OEM / non-branded way), the way our TV remotes use AA or AAA batteries. Whether it is AA or AAA does not really impede the design or function, and they work fine across brands, as they are all fundamentally using pretty much the same internal technology to change the TV stations with an IR beaming device.

Likewise, Sony, Bose, etc. are all doing headphones with around 20-30 hours playback and fundamentally similar hardware and software needs. So could they all run on a 800mAh ‘universal’ battery? I’d say yes. Indeed, some might say it would encourage better ‘energy management’ as they would have to be more efficient if they wanted to compete on having 5% more battery life for the same battery, which is not a bad challenge for R&D to undertake.

Fairphone x Duracell - Would This M&A Make Sense?

Suppose Duracell acquired Fairphone, or rather took a leaf out of their book - and produced a range of trusted, standardised LiPo batteries, as they do with Alkaline AA, AAA, etc.? If you were a startup like Yoto, would this mean that you might avoid the OEM hell of sourcing and certifying batteries from manufacturers - and instead just make it ready to receive one of say 3 battery sizes typically associated with music players and suchlike devices with similar power consumption? Is a secondary benefit that with economies of scale prices drop for all. With greater regulation and compliance are battery fires significantly reduced as the Battery Management Systems will then be designed by a few extremely proficient companies, and not a ‘WIld West’ of many different standards of manufacturers as there are right now. (I do not need to shame any companies, but if you’ve worked with LiPos in Product Design, you’ll know someone in the team who is very wary about ‘taking any chances’ with LiPos if you are not just making ‘cheap tat’, and are worried about your brand and reputation.

Another interesting thought would be if a company, let’s call them BigLiPo.com behaved like Apple, and issued a MFI Certificate to allow third parties to design systems and PCBs to be calibrated to work with their limited (but high quality) range of User Serviceable LiPo Packs? Does this remove a lot of anxiety and liability for small companies (and large), as well as reducing accidents overall? I have not conducted a comprehensive study, but certainly from phoning around designers across a diverse range of industries in my networks this is a real issue that would be great to alleviate pressure on.

Smartphone Batteries - But What About Waterproofing?

It seems ironic that we started out with Mobile Phones with user serviceable batteries, and although we have grown comfortable with the compactness of devices, and a degree of waterproofing (IP protection) that is impressive, it’s also fair to say that I am more likely to break my screen or exhaust my battery than to drop it in water deeper than a puddle (or worse a toilet on a night out), so really - is it impossible to create a good seal for a removable battery case?

Nobody would have believed a watch would be waterproof for 100m, and yet it is, even for sub-£30 prices. Granted you need to be in the £100 price range to have the battery as easy to remove as this Timex, (only need a coin to unscrew the back), and with the same 100m waterproofing, but it’s unquestionably possible with enough time and enthusiasm - and prices always fall once it’s been figured out. So it feels far too soon to bemoan that Fairphone has not nailed a 3m waterproof rating for a user replaceable battery just yet. I think it’s reasonable to think it will come - if a combination of consumer pressure/interest, and legislation is incentivising/forcing companies in the right direction.

Expanding outwards from just mobile phones again, my point here is that user serviceable ‘hatches’ or ‘doors’ will and can be made such that the integrity of products need not be presumed to be impossible to have safe, easy to change, and well sealed batteries.

~~~

Testing My Theories with Product Designer, Andrew Carr.

After all this immersion in details, I needed a trusted sparring partner - so turned to friend, and renowned product designer, Andrew Carr to give some perspective from his decades of experience, as well as just being great at testing ideas out. We both studied Product Design Engineering at Glasgow Uni / School of Art - and have kept in touch over the years. He’s had a varied career, from SpeckDesign to Plexus, and from SharkNinja to Elvie... and is soon to strike out in his own startup.

Huge thanks to Andrew for giving some superb insights into the Right to Repair discussion in general, and very much helping me move towards a conclusion (as much as one can have) on Right to Repair design advice, in the next section...

Up Next...

Contents:

Prologue:

Pre-Departure Notice - How an Attempt to Repair my Headphones Turned into a 3-Month Journey with a Grand Finale at the Recycling Centre.

Main Articles:

Intro - The Fight to Repair with Jude Pullen, for RS DesignSpark.

Part 1 - LiPo Battery Basics, Headless Laptops & Safety First.

Part 2 - Returning to Hong Kong, My Design Conspiracy Theories and Meeting Dr Lawrence.

Part 3 - Falling in Love With The Problem of R2R, Looria, and Pre-Purchase Reparability Considerations.

Part 4 - Ken Pillonel’s Ingenious iPhone Hack, and Repairability as a Disruptor.

Part 5 - Battery Post-Mortems with Andy Sinclair, Vapes, Dogmatism and Hacking My Headphones.

Part 6 - Legislation Loopholes, Eco Black Mirror, Chunky Fashion, and R2R Business Models and The Case for Standardisation.

Part 7 - Design, Engineering & Electronics Recommendations for R2R.

Encore:

Part 8 - Visit to End of Life Processing Plant - SWEEEP Kuusakoski Ltd

Part 9 - Interviews with Industry Experts on Right to Repair.

Contact: If you have any other questions, or would like to collaborate, please get in touch (link).

Disclaimer: This series has been created for discussion purposes and is not a 'how to' guide. Jude Pullen is a chartered engineering professional, and has sought additional expert advice alongside his endeavours to explore this subject safely. For additional information please see DS Terms of Use.

Comments