Machines as art exhibits?

Follow articleHow do you feel about this article? Help us to provide better content for you.

Thank you! Your feedback has been received.

There was a problem submitting your feedback, please try again later.

What do you think of this article?

Art critics have heaped praise on Mike Nelson’s exhibition, The Asset Strippers, which will be on display in the Duveen Gallery at Tate Britain until October 6th.

Journalists from publications ranging from The Guardian to Time Out have collectively described Nelson’s latest work as a sad lament for the decline of British manufacturing whilst at the same time eulogising about its understated and subtle allusions to artistic influences.

But it is not enough to say that The Asset Strippers is an expression of regret for the end of an era, simply looking sadly back on the nation’s industrial decline. Nor can this exhibition be viewed solely from the perspective of its artistic prowess.

Nelson’s work is a deliberate, undisguised and carefully timed warning to all of us, but more especially to British politicians. A warning that our past was built on our industrial and engineering heritage, and that lessons learned from our past must play a vital role in shaping our collective national future.

Lamenting The Past

Mike Nelson is a close friend of mine. We went to school together in Loughborough in the East Midlands and shared teenage years, drinking in the same pub every Friday and Saturday night, nurturing a love for the same music.

But what is more important than our friendship is what our family backgrounds have in common. It’s a background we share with many of our school friends – one based on industrial production.

It’s fair to say that industry caused our paths to cross. Throughout his working life, Mike’s father was employed in the textile industry, whilst my own father started work for the Electrical Engineering firm, Brush, in the early ’60s, before moving on to work in the Hawker Siddeley group which had acquired the company in the ’70s and ’80s. Industry rooted our families in the East Midlands, and there they stayed, gainfully employed.

But since those days, both industrial and textile production in the East Midlands has declined dramatically. In October 1960, Brush’s Falcon Works employed around 4,300 workers in its workshops, easily making it Loughborough’s biggest employer. Today, whilst Brush Turbogenerators continues to operate in the town, its employees number just a few hundred following an endless series of cost-cutting exercises and redundancies.

As for textiles, the decline of the local hosiery industry is typified by the fate of Leicester company, Corah, a firm which in 1960 boasted of a workforce of 6,500 after striking up a successful manufacturing partnership with Marks and Spencer’s in the 1950s. The company ran into financial difficulties in the 1980s, before being purchased by Coats Viyella in the early 1990s. The factory gates closed shortly afterwards.

The Corah story has been repeated across the East Midlands.

Machines Turned into Artefacts – The Abandoned Factory

The scene which greets me when I first enter Nelson’s exhibition is eerily clinical and quiet. Machines that the artist has recovered from failed companies over several months, if not years, have been carefully positioned on plinths made from heavy industrial equipment also recovered from redundant sites. For someone used to visiting production sites that are working, where a wall of noise hits you when you walk in, where movement and vibrant energy can be perceived from the first instant, the contrast with the Asset Strippers is sad.

It is as though I am walking into an Abandoned Factory, empty, arid, dead.

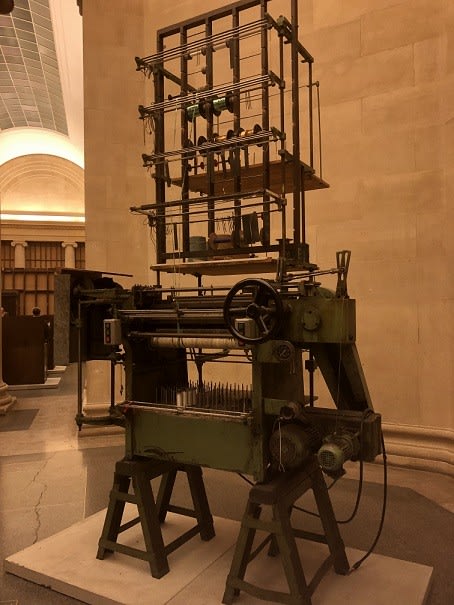

The scene is one of decay and decline. Dormant machines are at a standstill on rotting floorboards. What looks like punching and die casting machinery towers menacingly above me as I wander, heavy-duty lathes sit alongside welding equipment, chains, cement-mixers, weighing scales – the exhibits are animal-like, something akin to the extinct creatures you see on display in natural history museums, once full of terrifying power, now tamed, but still threatening. The dim light creates a melancholy atmosphere. All is quiet, the machines are silent. Their metal labels like the name tags you would come across in a zoo – Pollard, Leicester – Brush, Loughborough – Wadkin, Leicester – Dalton, Nottingham, all evidence of the strength of the industry in the East Midlands at the time when they were still active.

Machinery towers menacingly above me

At a certain point, the gallery widens to a circle where the light is stronger, and the processing machinery gives way to artefacts of a different kind: industrial racking reaches up above me; huge tracks removed from earth-moving vehicles have been positioned lizard-like, and most poignant considering Nelson’s family history, knitting machinery has been adorned with lurid thread creating a contrast between the bright colours and the cold, dead metal of the machines.

Bright colours stand out against the cold, dead metal of the machine

And as I walk further along the gallery, passing through roughly prepared, imposing timber barricades and into the final rooms, there are traces of the anonymous people who once worked in this Abandoned Factory, who worked the machines but who have since lost their livelihoods, their stories never told. It as though they were here a few minutes ago, but have just left the scene, their absence unexplained. Notes have been scrawled on cabinets, a sticker carries the manufacturer’s part number of a vital spare part, abrasive discs have been left on worktops and cabinet doors left open ready to reach into for components. In the final section of the installation, the artist has positioned what appears to be a decrepit, old tractor motor on top of a pile of used sleeping bags. The warning is stark: industrial failure impacts human lives.

Industry is not Art

But to say that The Asset Strippers is reminiscing regretfully over past glories and missed opportunities would mean taking in half the message. It would mean missing a critical irony of the exhibition. For me, the most important point I take from this display is a warning about the future, a warning that looking back at our glorious industrial heritage in the same way we view art, and artistic artefacts, will not help to safeguard and develop manufacturing at a time when it must be preserved. That manufacturing and production cannot be treated like art if it is to survive. That we need to learn lessons and carry them into our future.

By placing The Asset Strippers in the rarefied atmosphere of Tate Britain, where eccentric-looking art lovers are accustomed to gazing wistfully on carefully positioned artefacts that hark back to a lost colonial age, the artist is drawing parallels between our attitudes to art and industry, highlighting how we have come to look upon it as a quaint extra in our economy – unnecessary and interesting – yet not essential. (I reflect that the artefacts, the “assets” on display here have been carefully positioned in a formal, clinical way that mimics a classical art gallery). Once again, this is an ironic warning about our futures, not simply a sad reflection on a romantic past. I fear the irony will be lost on many who attend. Industry is not art, but the message here is that many in Britain have unconsciously arrived at the point where they see it as such and are happy and complacent enough to continue to do so. They see it as expendable, something to look at in an exhibition, not something that secures livelihoods.

The irony of The Asset Strippers lies in the fact it is an art exhibition.

Investment and Technology

And ironically, the Abandoned Factory I imagine I see before me in The Asset Strippers failed because it continued looking back to the past, living on its past glories. It failed to invest in the future.

Significantly, the machinery Nelson has collected is obsolete for a reason – it is old tech.

Successful businesses that have invested in new automation technology have kept the Asset Strippers at bay. For them, manufacturing is very much alive.

Here in the Duveen Gallery, we see nothing of the high-tech robotics that for the past five years have driven continuous increases in productivity at Jaguar Land Rover’s manufacturing site at Solihull. I suspect that new equipment installed to carry out research into hybrid engine charging at Toyota’s Burnaston production plant will never finish its life in an art exhibition. Also absent is the high-tech machinery and 3D CAD software now being developed and used by many of Leicester’s knitwear firms to increase quality and productivity. The tools used at Roll’s Royce’s On-Wing Research Technology centre situated at the University of Nottingham are not here, either.

Although sadly diminished, there is still some industry in the East Midlands that has not followed the Abandoned Factory in becoming obsolete. Industry that has invested in technology, but that requires investment to survive and that needs to be nurtured: Toyota, Fischer, Perkins Engines, Rolls Royce, 3M Healthcare – the list of those in this region who have survived and thrived because they invested in technology is long.

The Global Stage

Another warning issued by The Asset Strippers is about the dangers to industry caused by imposing barriers. The timber walls that Nelson has built, acting as blocks between rooms and the heavy industrial chains he has carefully draped at specific points across machinery, serve as metaphors, a carefully timed warning that producers cannot be restricted by barriers and need to be free to trade on a global scale. Pro-Brexit sentiment or anti? The important thing is to keep trading ties open.

Pollard, Leicester – Brush, Loughborough – Wadkin, Leicester – Dalton, Nottingham. All names of factories located within a few miles of each other, in the tight triangle of the country I grew up in between Leicester, Nottingham and Derby. Compare these to the words of Marvin Cooke, Managing Director of Toyota’s Burnaston production plant, interviewed by the BBC in September 2018: “Our just-in-time supply chain production relies on components imported from the EU. If just one supplier part is missing, we will not be able to produce cars during that time.”

In 2017, the Toyota plant produced 150,000 vehicles, 90% of which were exported to the European Union.

The contrast with the tightly-knit proximity of the factory location tags on these machines cannot be ignored – all from one local area – did those factories see the opportunities arising from trading on a wider, global scale? Failing to invest adequately in technology may have been what caused this Abandoned Factory and its machinery to finish up in Nelson’s exhibition, but equally, failure to work on a global scale, to see and benefit from the opportunities of free international trade would also have been fatal.

At a time when Brexit threatens to generate barriers, Nelson’s work issues a stark warning to all of us, not least our politicians and policy-makers.