Who are the History Makers? Part 3…

Follow articleHow do you feel about this article? Help us to provide better content for you.

Thank you! Your feedback has been received.

There was a problem submitting your feedback, please try again later.

What do you think of this article?

‘History Makers & DesignSpark’ is a brand new comedy podcast celebrating cutting-edge technology and the Makers from history who made it all possible, starring Dr Lucy Rogers and the award-winning comedians Bec Hill and Harriet Braine. We take a quick peek at what defined the Makers in question in a short series of articles.

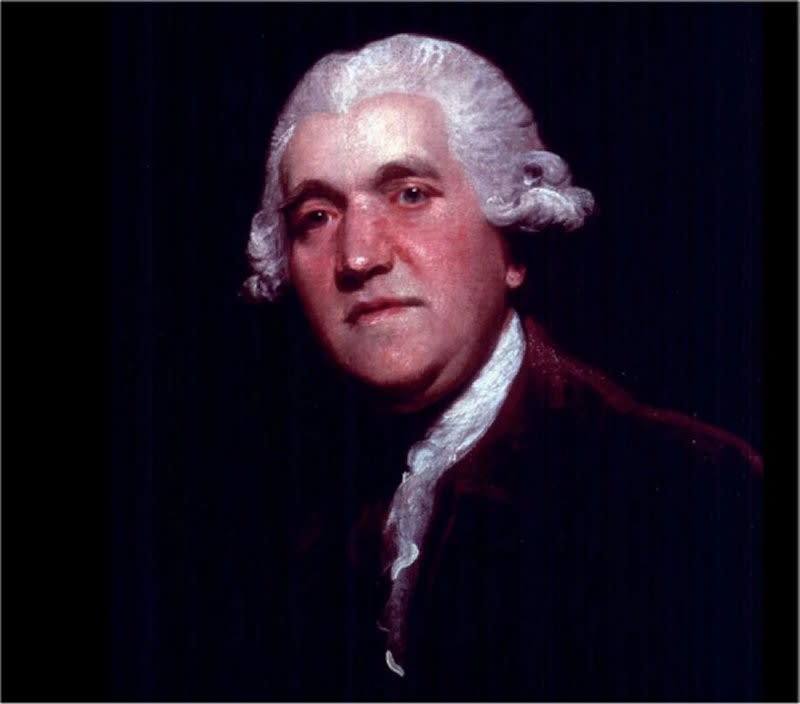

Josiah Wedgwood, Master Potter

Josiah Wedgwood came to be on the 12th of July 1730 at Burslem in Staffordshire, the last child of eleven children born to Thomas and Mary Wedgewood. The family were a busy assembly of Potters and at an early age, Josiah was proving to be very skilled in the craft.

After his father's death in 1739, he began working as a 'thrower' in the family business under the apprenticeship of his eldest brother, Thomas. After a serious case of smallpox left Josiah with a weakened right leg this ultimately meant he had to abandon throwing, he instead turned his talents to designing pottery. At the time, the family business produced relatively low-quality merchandise that was inexpensive to buy.

Seeking the Chemistry

As he became older Josiah naturally expected a partnership within the family business, but, his elder brother refused and so the young Josiah moved first to a small pottery business run by John Harrison, and then on to be a partner in a pottery business owned by Thomas Whieldon. Josiah began studying the then new-science of Chemistry, seeking to develop better manufacturing methods, improve the clays and materials used and to enhance the poor pottery of the day and bring some much-needed innovation to the process.

After meeting Joseph Priestley, who gave him valuable advice concerning chemistry, he opened a pottery works of his own, first the Ivy Works in his hometown of Burslem and later at the Brick House factory. While at these establishments Josiah designed and created many models and also prepared alternative clay mixes as he refined his ideas.

Improving the plate

Wedgwood, with his keen interest in science, greatly improved upon the plain and ordinary crockery of the day, introducing durable, simple and regular wares. His cream coloured earthenware was christened 'Queen's Ware' after Queen Charlotte, who had appointed him the Queen's potter in 1762. Anything Josiah made for the Queen was automatically exhibited before it was delivered leading to his first overseas orders, business was certainly booming.

The original Bottle Kiln Ovens at Etruria

Around 1765 Josiah opened a warehouse in Charles Street, located in Mayfair, London, and it soon became an integral part of his sales organisation. The tastes of the society of the time were changing and Josiah reacted to these demands, perfecting black stoneware which he called basalt, using it to create intricate vases. His Smallpox weakened knee continued to give him trouble throughout his lifetime and in 1768 he was forced to have it amputated. In June of 1769, he opened a new factory at Etruria, near Stoke-on-Trent, in partnership with the established potter Thomas Bentley. They worked together for a decade and during that time and thanks to a cash injection from Josiah’s richly endowed wife, the first true pottery factory was born. Attached to this factory was a village where Josiah’s workmen and their families could live in decent surroundings, a boon for the workers of the day.

Barium Sulphate Experiments

Jasperware Vase. Image source: V&A Collections

Josiah Wedgwood experimented with barium sulphate for around 2 years and from those experiments, in 1773, he created Jasperware. Jasperware blends metallic oxides, most often blue in colour and features white moulded reliefs and is what many people recognise as Wedgewood Pottery today.

Josiah was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1783, the main reason this was for his invention of the pyrometer which measured oven temperatures. He also took a keen interest in efficient factory organisation and in improving the transport of raw materials and finished wares by canals, such as the Grand Trunk Canal, which he also backed financially along with other industrial ventures. When his long-term business partner, Thomas Bentley, died in 1780, he asked his friend Erasmus Darwin for help in running the business, and he duly obliged. Erasmus’s son would later go on to marry Josiah’s daughter, who would turn out to be the parents of Charles Darwin, the naturalist who formulated the theory of evolution. Charles Darwin would himself, as it turned out, would later marry a Wedgwood.

Abolitionist campaign medallion, Image source: V&A Collections

Josiah was, from 1787 until 1795 an active abolitionist, campaigning for the end of slavery and his pottery ‘Slave Medallion’ was produced in huge quantities and distributed far and wide, often worn by fashionable ladies as a brooch, or fashioned into a hairpin. Sadly, after decades of tireless work as both a world-defining potter, industrialist and in his later years as a campaigner for social reform, Josiah Wedgewood died on 3rd January 1795 from suspected jaw cancer, he left a thriving business and a fortune to his surviving children.

Ada Lovelace and the First Computer Program

On the 10th of December 1815, Augusta Ada King-Noel, Countess of Lovelace, or simply Ada Lovelace to you and me, was born in London. She was the only legitimate child of the famous poet Lord Byron and his then-wife Annabelle Milbanke. Byron separated from his wife just a month after Ada was born, it’s said he was disappointed that she wasn’t ‘the glory boy’ he yearned for, he died in 1824 when Ada was just eight years old, having had nothing to do with her throughout those years.

Pushing Mathematics

Ada’s mother Annabelle didn’t have a particularly close relationship with her daughter it seems, often leaving her in the care of her own mother. Annabelle held a burning resentment for her former husband’s behaviour, which may have been one of the reasons for the distance she placed between herself and Ada. Ada’s mother, however, was very keen in certain aspects of her daughter’s upbringing constantly pushing Ada’s skills in mathematics in an attempt to prevent her from developing the ‘insanity’ displayed by her father Byron.

Like many children of the day, Ada was often ill and in June of 1829, she was paralysed after a serious episode of measles and consequently spent nearly a year confined to her bed, which may have hindered her recovery to a degree. 3 years later she was finally able to walk on crutches and despite the ravages of her illness, she had been busy honing her mathematics and logic skills.

Babbage Difference Engine in the London Science Museum

As a teenager, Ada was presented at court and went on to become a ‘popular belle of the season’ because of her natural grasp of complex mathematics and pleasant manner. Ada was a popular figure at court, both charming and intelligent, she made many acquaintances including the scientists Andrew Cross, Charles Wheatstone, Michael Faraday and others. Her keen interest in mathematics began to mature and would go on to dominate her adult life.

Ada became friends with her private tutor Mary Somerville who introduced her to Charles Babbage in 1833, he invited Ada to see the prototype for his Difference Engine. She became fascinated with the machine and visited Babbage as often as she could. Babbage was likewise impressed by Lovelace's intellect and analytic skills, calling her ‘The Enchantress of Number’

The Analytical Engine Notes

Diagram of an algorithm for the Analytical Engine for the computation of Bernoulli numbers, from the Sketch of The Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage by Luigi Menabrea with notes by Ada Lovelace

During 1842 to 1843 Ada translated the Italian Mathematician (who later went on to become the Prime Minister of Italy in 1867-69), Luigi Menabrea’s article on Baggage’s latest machine proposal, the Analytical Engine. Ada created a set of complex notes, explaining that the Analytical Engines function was a very complex task and a difficult concept to fathom. The notes that Ada created contained what many consider to be the first computer program ever written as well as expressing a vision of the capability of the Analytical Engine to go beyond the calculation of mere numbers.

These notes were three times longer than the actual article itself and included a method for calculating a sequence of Bernoulli numbers, which could have run correctly had Babbage's Analytical Engine ever been built. Ada stated in her notes…

‘The Analytical Engine might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations, and which should be also susceptible of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism of the engine. Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent’

Original Daguerreotype of Ada Lovelace

Defining the Computer

While Babbage and others concentrated solely on the computational abilities of machines, Ada saw something else, that numbers could represent entities rather than simply quantities. Once a machine could manipulate symbols, which numbers are, what if those symbols represented differing things, such as musical notes or letters, you then move on from a number-crunching machine to a computational device.

After her work with Babbage Ada continued to work on numerous projects, including fads of the day that included Phrenology and mesmerism and in 1844 she confided in her friend Woronzow Greig about her desire to create a mathematical model for how the brain gives rise to thoughts and nerves and feelings. As part of her research, she contacted an electrical engineer Andrew Crosse to learn how to carry out electrical experiments. Sadly, before she could continue her quest, Ada died at the young age of 36, the same age as her father Lord Byron, in 1852. She was buried alongside her father at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Hucknall, Nottinghamshire, England.