An intro to Linux file system management

Follow articleHow do you feel about this article? Help us to provide better content for you.

Thank you! Your feedback has been received.

There was a problem submitting your feedback, please try again later.

What do you think of this article?

When migrating from another operating system such as Microsoft Windows to another; one thing that will profoundly affect the end user greatly will be the differences between the filesystems.

What are filesystems? How Linux filesystem is different than Windows?

A filesystem is the methods and data structures that an operating system uses to keep track of files on a disk or partition; that is, the way the files are organized on the disk. The word is also used to refer to a partition or disk that is used to store the files or the type of the filesystem. Thus, one might say I have two filesystems meaning one has two partitions on which one stores files, or that one is using the extended filesystem, meaning the type of the filesystem.

The difference between a disk or partition and the filesystem it contains is important. A few programs (including, reasonably enough, programs that create filesystems) operate directly on the raw sectors of a disk or partition; if there is an existing file system there it will be destroyed or seriously corrupted. Most programs operate on a filesystem, and therefore won't work on a partition that doesn't contain one (or that contains one of the wrong type).

Before a partition or disk can be used as a filesystem, it needs to be initialized, and the bookkeeping data structures need to be written to the disk. This process is called making a filesystem.

Most UNIX filesystem types have a similar general structure, although the exact details vary quite a bit. The central concepts are superblock, inode, data block, directory block, and indirection block. The superblock contains information about the filesystem as a whole, such as its size (the exact information here depends on the filesystem). An inode contains all information about a file, except its name. The name is stored in the directory, together with the number of the inode. A directory entry consists of a filename and the number of the inode which represents the file. The inode contains the numbers of several data blocks, which are used to store the data in the file. There is space only for a few data block numbers in the inode, however, and if more are needed, more space for pointers to the data blocks is allocated dynamically. These dynamically allocated blocks are indirect blocks; the name indicates that in order to find the data block, one has to find its number in the indirect block first.

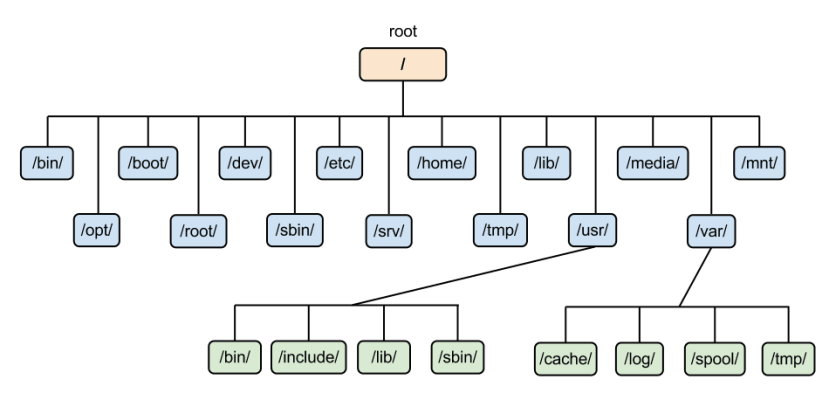

Like UNIX, Linux chooses to have a single hierarchical directory structure. Everything starts from the root directory, represented by /, and then expands into sub-directories instead of having so-called 'drives'. In the Windows environment, one may put one's files almost anywhere: on C drive, D drive, E drive, etc. Such a file system is called a hierarchical structure and is managed by the programs themselves (program directories), not by the operating system. On the other hand, Linux sorts directories descending from the root directory / according to their importance to the boot process.

If you're wondering why Linux uses the frontslash / instead of the backslash \ as in Windows it's because it's simply following the UNIX tradition. Linux, like Unix also chooses to be case sensitive. What this means is that the case, whether in capitals or not, of the characters, becomes very important. So this is not the same as THIS. This feature accounts for a fairly large proportion of problems for new users especially during file transfer operations whether it may be via removable disk media such as a floppy disk or over the wire by way of FTP.

The filesystem order is specific to the function of a file and not to its program context (the majority of Linux filesystems are 'Second Extended File Systems', short 'EXT2' (aka 'ext2fs' or 'extfs2') or are themselves subsets of this filesystem such as ext3 and Reiserfs). It is within this filesystem that the operating system determines into which directories programs store their files.

If you install a program in Windows, it usually stores most of its files in its own directory structure. A help file for instance may be in C:\Program Files\[program name]\ or in C:\Program Files\[program-name]\help or in C:\Program Files\[program -name]\humpty\dumpty\doo. In Linux, programs put their documentation into /usr/share/doc/[program-name], man(ual) pages into /usr/share/man/man[1-9] and info pages into /usr/share/info. They are merged into and with the system hierarchy.

Unless you mount a partition or a device, the system does not know of the existence of that partition or device. This might not appear to be the easiest way to provide access to your partitions or devices, however, it offers the advantage of far greater flexibility when compared to other operating systems. This kind of layout, known as the unified filesystem, does offer several advantages over the approach that Windows uses. Let's take the example of the /usr directory. This sub-directory of the root directory contains most of the system executables. With the Linux filesystem, you can choose to mount it off another partition or even off another machine over the network using an innumerable set of protocols such as NFS (Sun), Coda (CMU) or AFS (IBM). The underlying system will not and need not know the difference. The presence of the /usr directory is completely transparent. It appears to be a local directory that is part of the local directory structure.

Here is a good article to read more on Linux filesystem.

List of 19 Essential Linux Folders

Here is the list of 19 essential folders. Go to each folder link to learn it in depth:

- The Root Directory

- /bin

- /boot

- /dev

- /etc

- /home

- /initrd

- /lib

- /lost+found

- /media

- /mnt

- /opt

- /proc

- /root

- /sbin

- /usr

- /var

- /srv

- /tm